Let’s get some definitions out of the way, shall we?

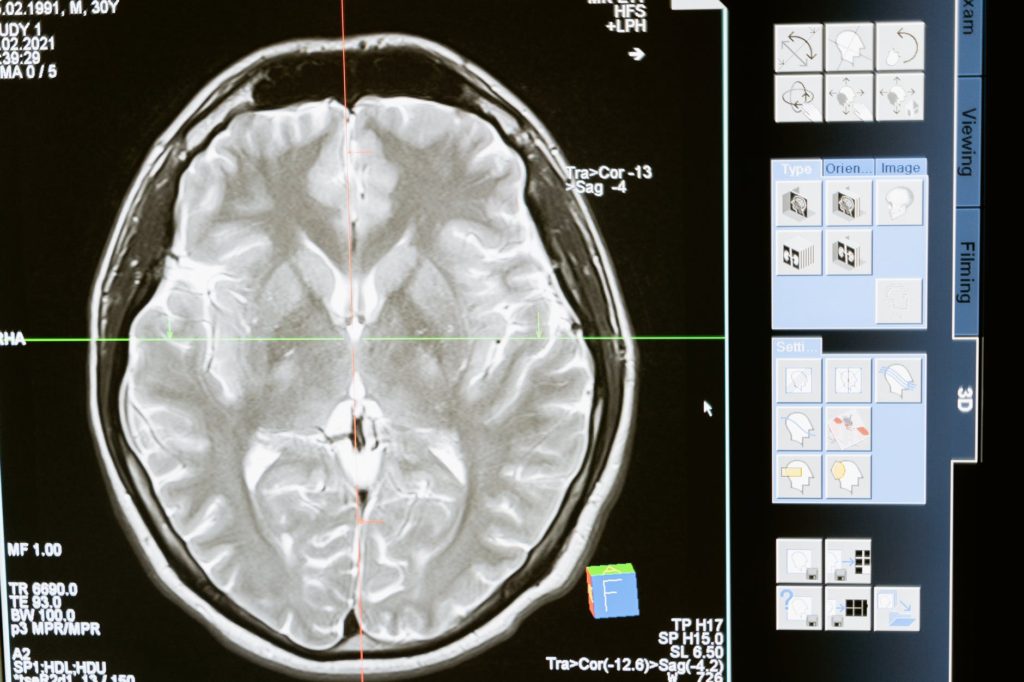

Amygdala: The brain structure that detects stress and tells the HPA axis to respond. Prefrontal Cortex: The control center of the brain that controls thoughts and actions. Its main job is to control the emotional responses to stress by regulating the amygdala. Hypothalamus–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) Axis: The messenger system that begins in the brain. It signals the organs to react to stress by going into survival mode. It includes the hypothalamus, the pituitary, and the adrenal gland.

Now, grant me creative license to discuss the brain. I am going to rename the amygdala Amy G. Dala. My view is that when Amy detects a threat, she immediately prepares one to fight or to take flight. Amy was exceptionally useful for my troglodyte ancestors as they constantly faced severe threats any time they left their caves–all kinds of animals who wanted to eat them, other troglodytes who wanted to kill them, and natural forces for which they were ill-prepared, for example. Today, in the United States, I don’t face such a threatening world. Amy, however, still resides within me, and she’s as trigger happy now as she was for my Neanderthal forbears. I need to deal with Amy because she makes me too reactive.

Amy G. Dala Winning

Let’s look at an example of Amy in action from my beach vacation, this summer. I got up early one morning to walk Wilbur, Griffin, and Buddy, our three Chihuahuas. We walked along a paved path pinned between a guardrail to the right that protected us from road traffic and a fence to the left that separated us from a cliff that dropped down to the beach. I did my best to rein in the pooches whenever I saw someone coming to enable them to get around us. When the path was clear, I let the dogs wander a bit on their leashes.

Unbeknownst to me, a jogger was coming up fast behind us. Without slowing down, he hopscotched through my small web of tangled leashes and my dogs, and yelled, “You can’t take up the whole path with your dogs!”

Amy within me immediately reacted, and I shouted, “Next time just say, ‘Excuse me!'”

The man responded by giving me the middle finger as he continued jogging to which I yelled, “Really classy. Where’s your trailer?” Thankfully, the jogger kept on jogging.

In this incident with the jogger, my prefrontal cortex didn’t stand a chance against Amy’s speed at triggering a response to a stressor. Fighting words had unconsciously and immediately spewed from my mouth. My response to the jogger was at best useless and at worst scary. My response scared me for two reasons. First, it could have further escalated the situation to violence. Second, my response was an unconscious response. An unconscious response might be okay during a sporting activity or when facing a real threat, but in most contexts it simply means we are out of control, and that’s frightening.

Prefrontal Cortex Winning

Generally, it would be preferable for Amy to defer to the prefrontal cortex. Here’s an example of the prefrontal cortex taking charge of a different incident at the beach. My wife and I set up chairs on the sand. Within a few minutes a young man emerged from the ocean with his surfboard, and asked us to move. He pointed to his beach blanket and umbrella behind us and said he was set up right there. He was polite, and I think because of that Amy in my head did not jump into action.

However, I was befuddled by the young man’s request; what did it matter that we were between his spot and the water? Couldn’t the guy just walk around us? Amy was starting to stir but my prefrontal cortex seemed to be cranking up, too. My prefrontal cortex wanted to calm Amy down.

As the war between Amy and my prefrontal cortex began, my wife simply replied to the surfer, “Sure,” and moved over a few feet. She had engaged her prefrontal cortex before me, assessed the situation, and decided it was simply easiest to move. I followed her lead.

“Thank you,” the surfer said, and everyone went about enjoying the beach. Clearly the result of my wife using her prefrontal cortex was superior to that of my Amy causing an unnecessary disturbance on the beach.

The Plan to Assist My Prefrontal Cortex in the War!

I. Deliberate Pause

My military aid package to my prefrontal cortex in its war with Amy includes training myself in the art of the deliberate pause. Most “threats” that I face in modern day U.S.A. are not really threats at all; usually they are just words or petty behaviors. Accordingly, I have the luxury of not needing to react quickly or to react at all. By using a deliberate pause when agitated or provoked, I can give my prefrontal cortex that little bit of extra time to triumph over Amy in daily battle.

II. Meditation

When not on the frontlines of battle, I can use meditation to prepare for the conflicts ahead. Scientific Studies have shown that meditation can:

- Activate and thicken the prefrontal cortex

- Increase grey matter density in the prefrontal cortex

- Strengthen the connection between the prefrontal cortex and the amygdala

- Shrink the amygdala

- Prevent the prefrontal cortex from shrinking

Meditation = prefrontal cortex stronger; Amy weaker. Good.

III. Religion

Every war should have religion dragged into it, should it not? While religions have been used and abused by people in every generation all over the world, they are also full of wisdom, including concepts helpful in my prefrontal cortex’s war against Amy.

Deliberate pause? How about this:

“My dear brothers and sisters, take note of this: Everyone should be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry.”

James, 1:19 (NIV).

Meditation? Buddhists and Hindus have been doing it for thousands of years. Nice for science to catch on.

Don’t like religion? How about philosophy? The Stoics had a lot to say that would be helpful in the war against Amy.

“Anger, if not restrained, is frequently more hurtful to us than the injury that provokes it.”

Seneca, 4 BC – 65 AD, Roman Stoic Philosopher

“No man is free who is not master of himself.”

Epictetus, 55 – 135 AD, Greek Stoic Philosopher

“You have power over your mind – not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength.”

Marcus Aurelius, 121 – 180 AD, Roman Emperor and Stoic Philosopher

At any rate, I’ll continuously arm my prefrontal cortex by staying engaged in religious and philosophical study.

Conclusion

I have read that the prefrontal cortex shrinks as we age. As a middle-aged man, it will be especially important for me to be vigilant against Amy’s dark side by bolstering my prefrontal cortex against her as best I can. I will use deliberate pauses, meditation, and nuggets of wisdom from religion and philosophy to aid me. What’s your plan?

With Love,

P. Gustav Mueller, author of The Present